Here, finally, is the test of the Commodore PET CBM 8032 that I had bought on eBay in the United States and which I had told you about in this video. I found a way to power it at 110V!

I hope you can get some ideas if you need to power some of your computers that run at 110V.

Power a computer at 110V

Computers arriving from the United States run at 110 Volts 60 Hertz. In particular, the Commodore PET CBM 8032, which I bought on eBay in the States, runs at 117V 60Hz, consuming just over 100W.

I found this transformer on Amazon: the Bronson++ VT-300. It transforms 220V to 110V, but does not change its frequency, which remains at 50Hz.

The Bronson++ VT-300 transformer has a power of 300 Watts (200W continuous), so it is suitable for the power drawn by the Commodore PET CBM 8032, which consumes just over 100W.

At the rear, it has the power input. The power input voltage can be set via a selector: 110V, 200V, 220V, 240V RMS.

Up front, the Bronson++ VT-300 has two outputs: one 240V with UK plug, one 110V with US plug. By selecting the 240V power input, the front output is about 105V.

What happens if I power a 110V 60Hz to 50Hz transformer?

Before testing the Commodore PET, CBM8032, to be more aware, let's study some transformer theory!

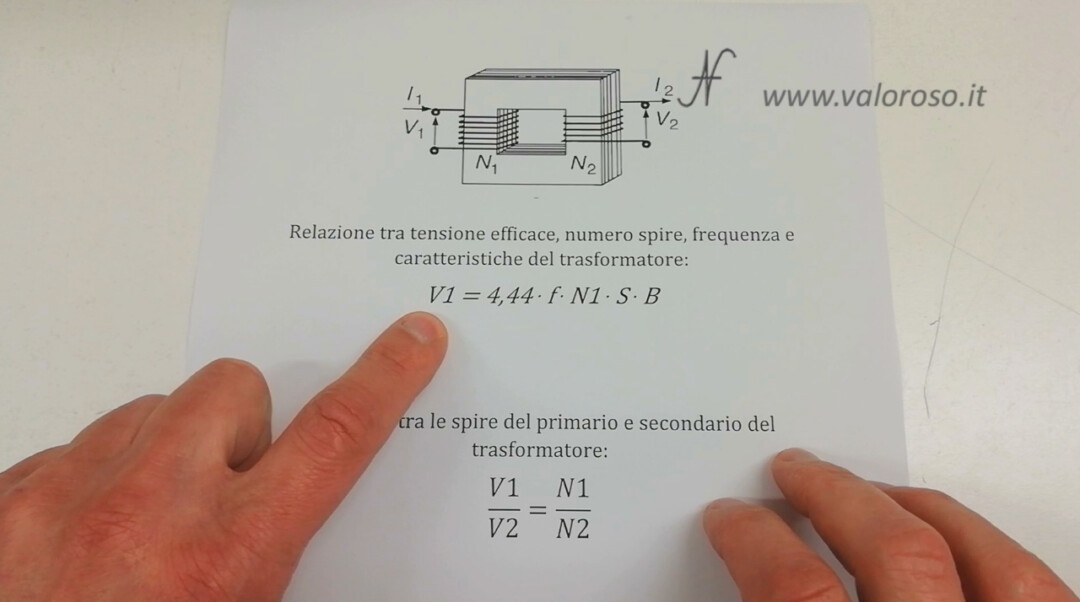

A transformer is formed by a primary winding, the one we connect to 220 Volt or, in the case of my PET, to 110 Volt 60 Hertz, and one or more secondary windings.

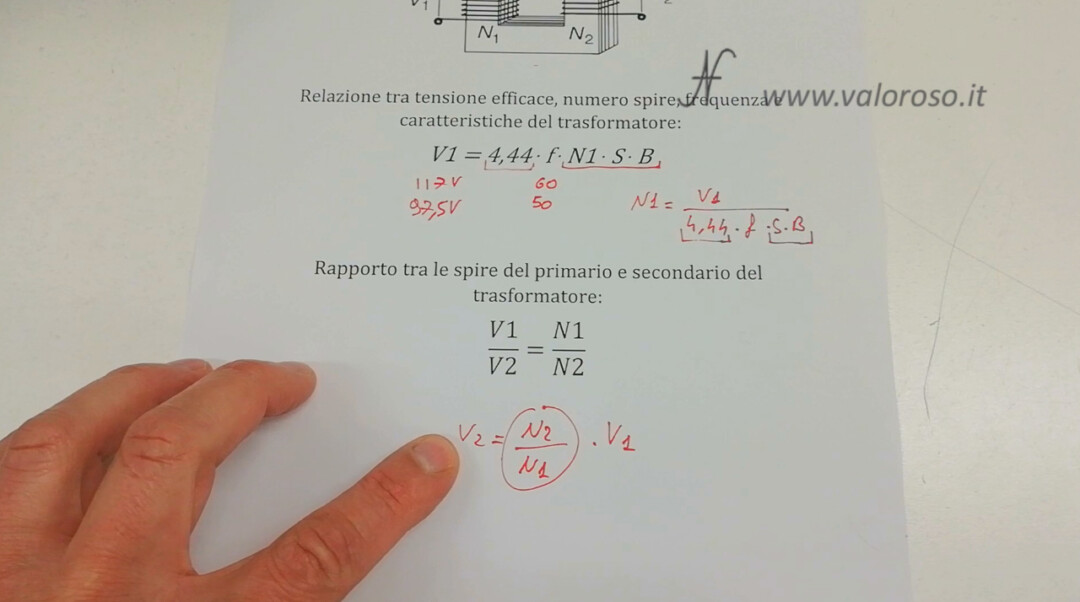

The windings are magnetically connected to each other via the air gap. The first equation we see is related to the nominal voltage of the primary winding (V1).

V1 = 4,44 * f * N1 * S * B

The rated voltage of the primary winding (V1) depends on the frequency f, by the number of turns N1 of the primary winding and other factors that we will see shortly.

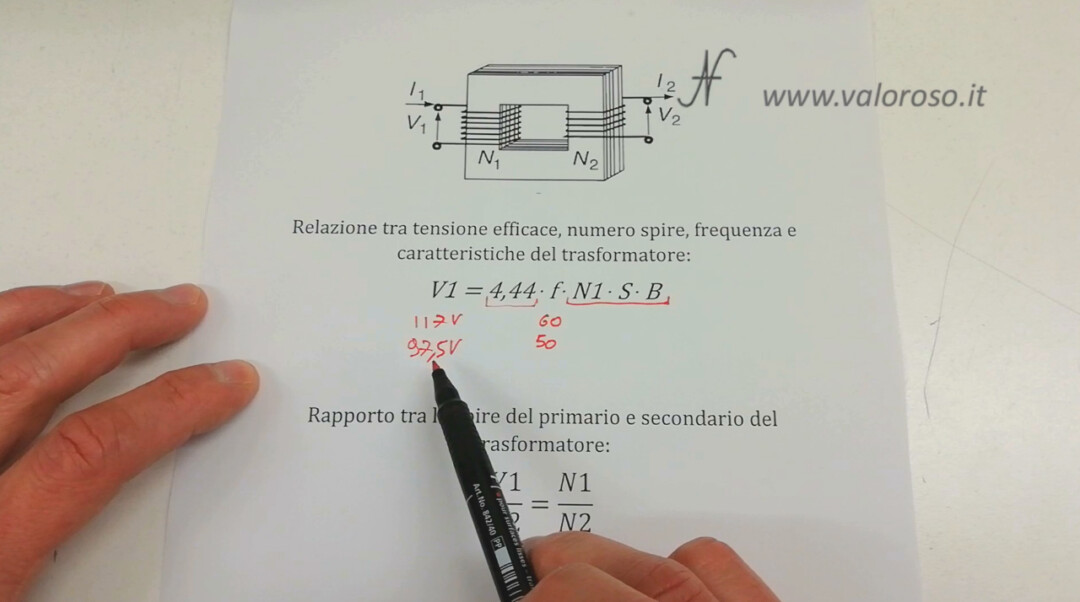

In this case, the rated voltage of the primary winding (V1) is 117 Volt, we read it from the rear plate of the Commodore PET CBM 8032. The three factors (N1 * S * B) are constant, because we do not modify the transformer:

- N1 is the number of turns of the primary winding;

- S and B represent the shape and material of the metal.

4.44 is a number, that is, a constant by definition.

So, if V1 is equal to 117 volts effective at 60 hertz, we see that, by lowering the power frequency to 50 Hertz, the voltage of the primary winding is consequently also lowered, which then passes to 97.5 volts in alternating, RMS.

Here, it is as if we no longer find a 117 Volt transformer, but, rather, a transformer of just under 100 Volts, which we have to power with just over 100 Volts. Somehow, we are a bit comfortable that the Bronson++ VT-300, which I bought on Amazon, gives me an output voltage of 105 Volts, instead of 110V.

This is because it is a little close to the nominal voltage of the "new" Commodore PET transformer that we imaginatively created, bringing the supply voltage from 60 Hertz to 50 Hertz.

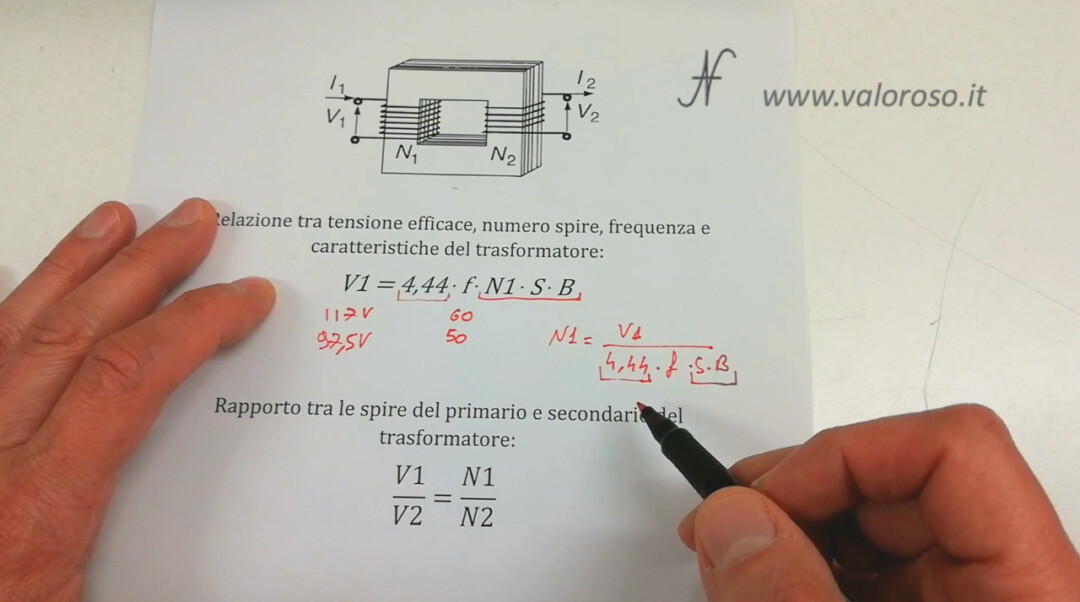

We can also make another reasoning: what would it take to bring this transformer back to 110 volts nominal? Let's reverse the formula.

N1 = V1 / (4,44 * f * S * B)

We have already said that S and B they are constant. Suppose we want to keep it constant too V1, the nominal voltage of the primary of the transformer of the Commodore PET.

At this point, we realize that we should increase N1, the number of turns of the primary winding, because, if we reduce the frequency (f) from 60 to 50 Hertz, which is found in the denominator (under the fraction), simultaneously increases the number of turns by 20 percent N1 of the primary winding.

Obviously it's just theory, as we can't physically increase the turns of the Commodore's transformer.

Keeping the Commodore transformer supply voltage lower, then from 117 V to 105 V coming out of the Bronson++ VT-300, obviously it will also lower the voltage at the secondary of the transformer a little (V2), because the relationship between the coils N1/N2 of the primary and secondary is constant (we are not going to modify the PET transformer).

V2 = (N2/N1) * V1

Hence, lowering V1 (the voltage of the transformer primary), it also lowers V2 (the voltage of the secondaries).

We have two possibilities:

- if we keep the primary voltage of the PET transformer at 117V, when this is not designed to do so, because the mains frequency is at 50Hz against 60Hz, the transformer could heat up;

- by lowering the voltage at the primary winding too much, we will also have a lowering of the voltages at the secondary windings, which may not be sufficient for the PET voltage regulators.

With the Bronson++ VT-300 bought on Amazon, we put the input voltage more or less in between these two situations. We try to minimize the thermal effect on the Commodore's transformer, keeping the voltage lower V1, but we try not to lower it too much V2.

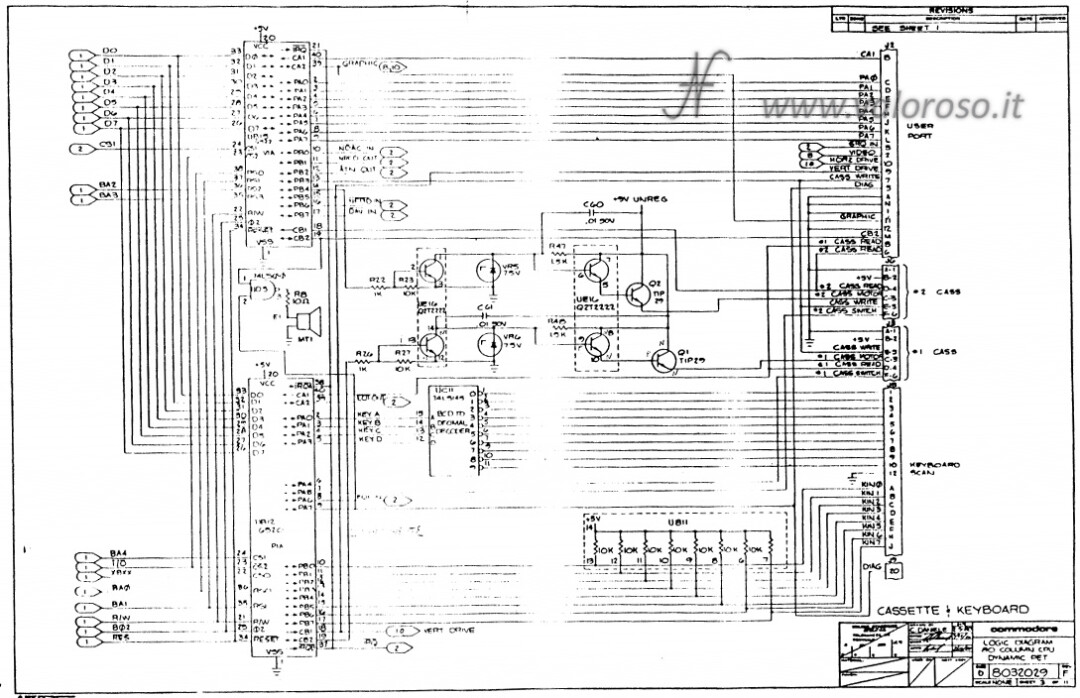

Wiring diagrams of the Commodore PET power supply, CBM 8032

How does this affect the Commodore PET?

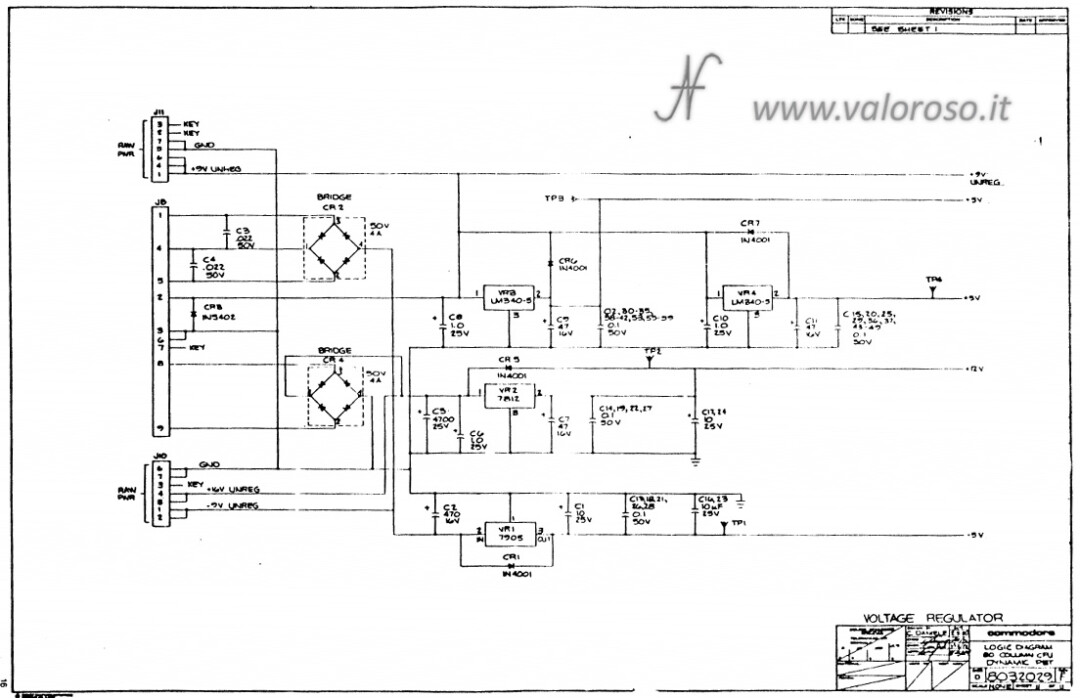

Let's analyze the wiring diagram of the Commodore PET power supply.

The secondaries of the PET transformer go to rectifier bridges and the AC voltage is rectified and smoothed by the capacitors. At this point, after it has been straightened and smoothed, the voltage no longer has the frequency: neither 50 Hertz nor 60 Hertz. It has frequency 0, since it is a direct voltage!

Subsequently, the rectified and smoothed voltage goes to the various voltage stabilizers: LM340-5, 7812, 7905, which regulate the various direct voltages (5V, 12V and -5V) necessary for the functioning of the motherboard of the CBM 8032.

From the schematic, I don't see a criticality in lowering the frequency from 60 to 50 Hertz because nowhere does this frequency pass. At the limit, keeping the voltage at the input of the regulators a little lower, it is possible that the voltage is too low compared to what is necessary. However, later, when we feed the PET, we will check that the regulated voltages are actually the correct ones.

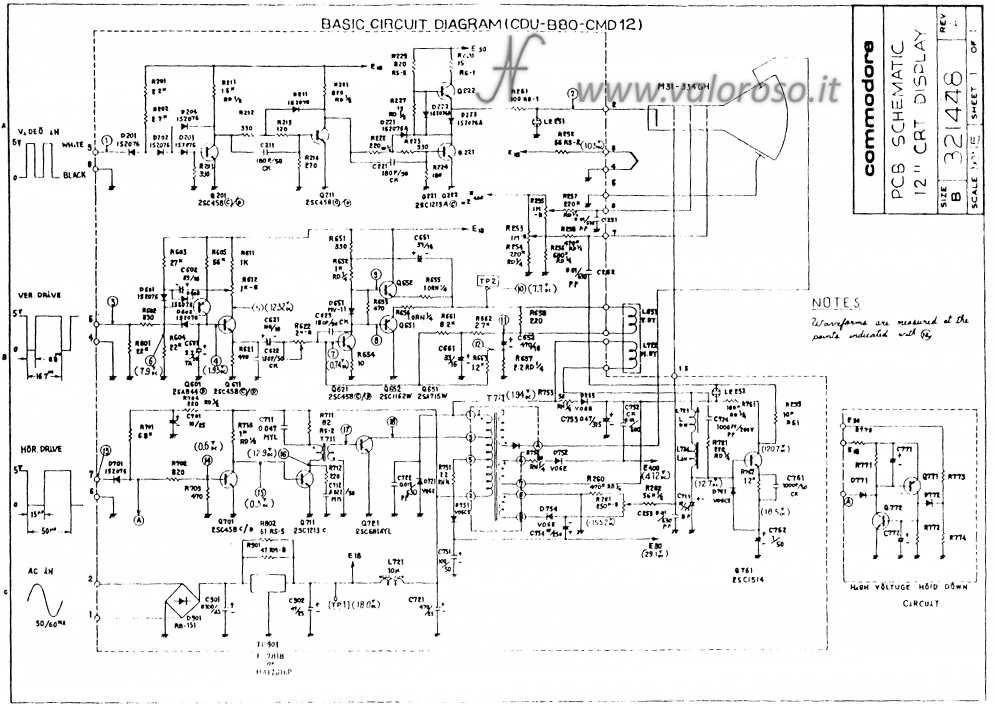

There is another socket on the secondary of the transformer, which is the one that goes to the PCB of the CRT.

The alternating power supply voltage enters the point indicated at the bottom left of the CBM 8032 wiring diagram. You see that it is written: 50/60 Hertz which means the card is set up for both frequencies. Indeed this is true, because the voltage is straightened, leveled and adjusted, as we have seen previously.

That said, I feel pretty confident that my Commodore PET will work by the time I feed it with a voltage of 50 Hertz, rather than 60 Hertz.

Connect the Commodore PET, CBM 8032, to the power supply

To test the Commodore PET, CBM8032, we can proceed to make the electrical connections. The power plug of the computer must be connected to the front 110V socket of the Bronson++ VT-300.

The rear power input of the Bronson++ VT-300 connects to the 220V 50Hz mains socket.

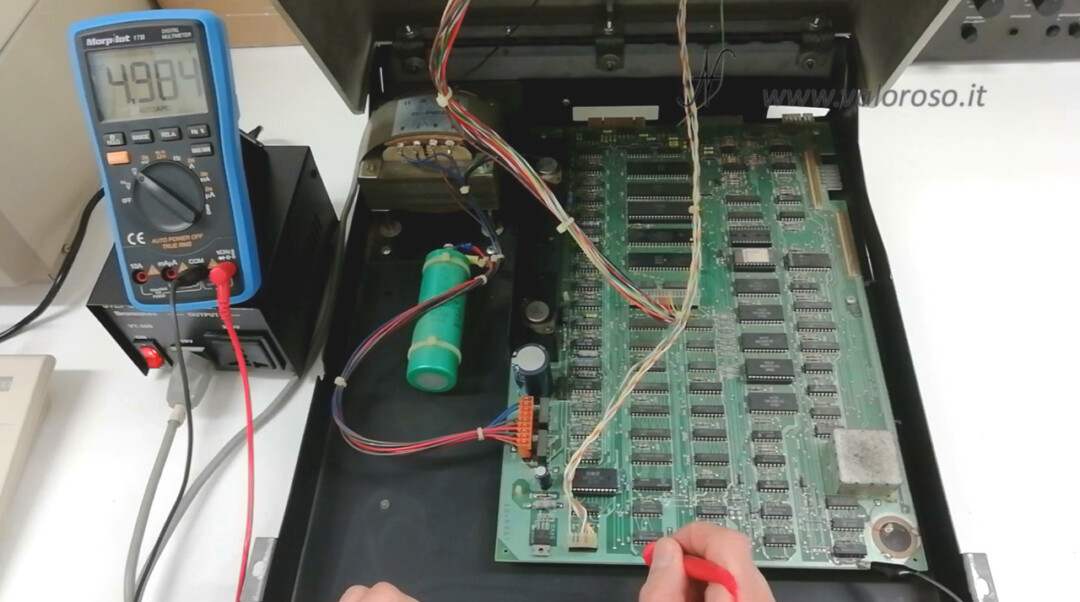

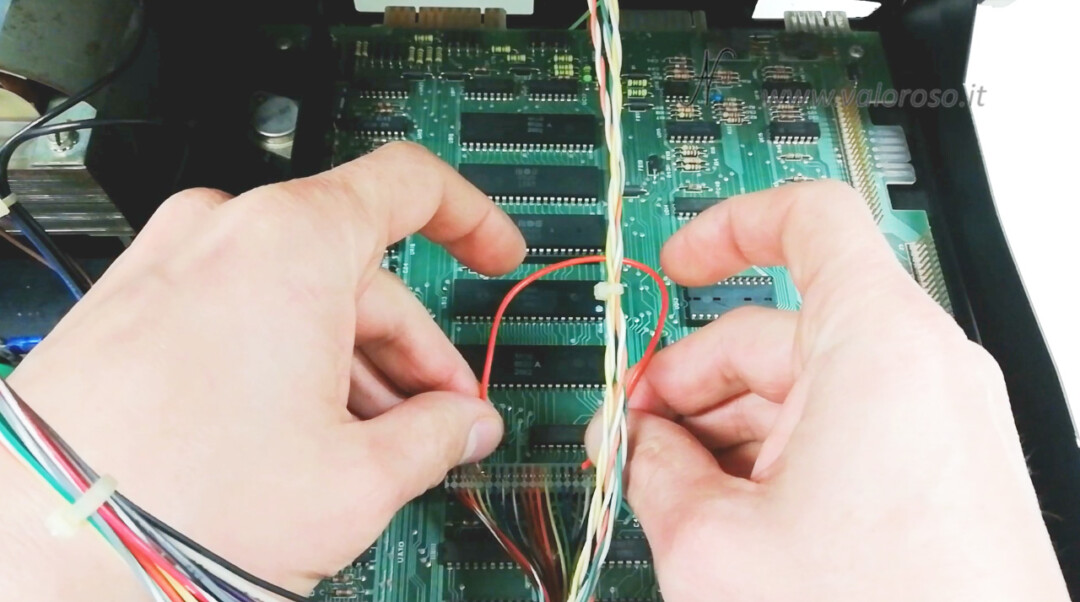

For the sake of consideration, we also open the computer, to measure, with the tester, the various DC voltages after we have turned it on. We have seen in the previous article how to open the Commodore PET, CBM8032.

We light up?

The rear switch of our Commodore PET CBM8032 is already set to ON. You also need to turn on the Bronson++ VT-300.

It is time to power the Commodore PET, CBM 8032

The Commodore PET, CBM 8032 emits the classic start-up sound! He's gone!

The power supply voltage is correct. The tester is connected to 5 Volts, which is one of the most critical voltages inside a computer: it must be regulated correctly because, if it is too high, it burns all the integrated circuits.

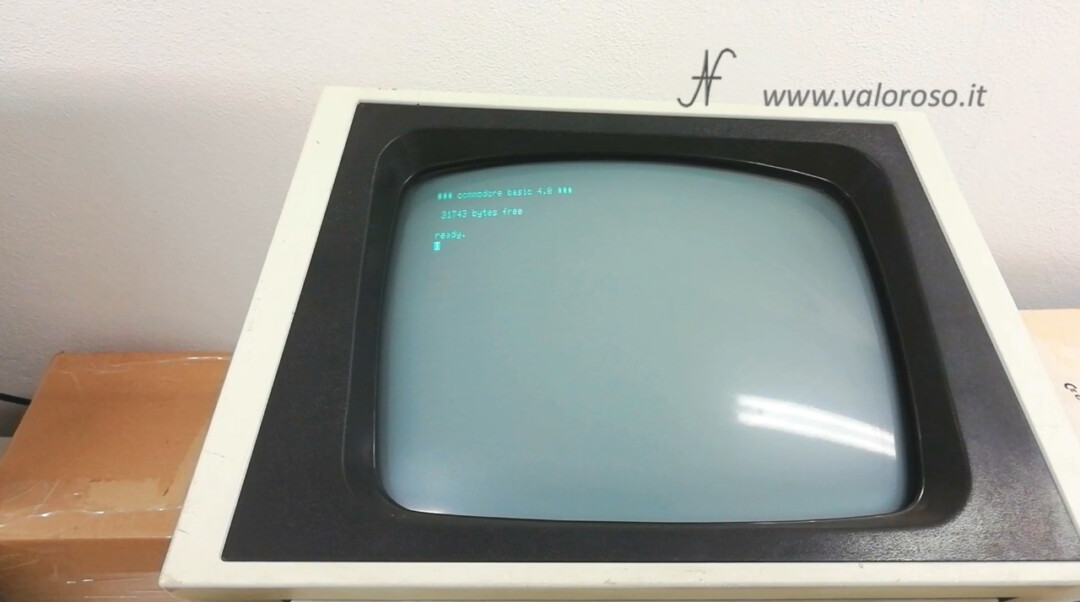

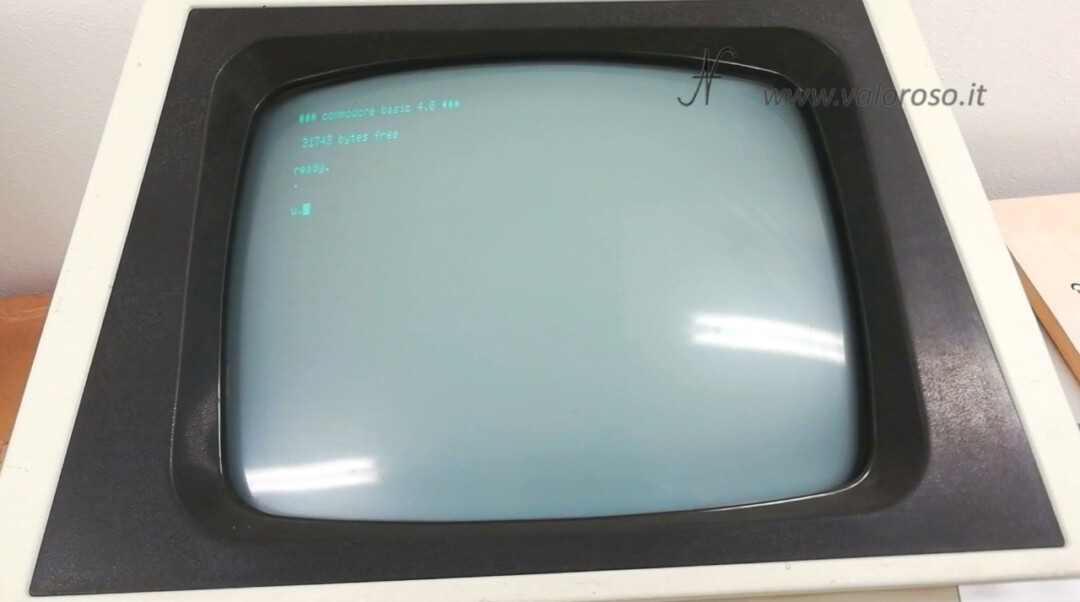

The monitor shows some writing! Fantastic!

Better to turn off the computer immediately: you need to give the capacitors time to regenerate. After a computer (but also a stereo system, a radio, etc.) remains turned off for a long time, the capacitors need a little voltage, but also a little rest! I'll explain it in this article.

After a few minutes of rest, we can turn the computer back on and try all the other power supply voltages: 5V, -5V and 12V again.

We can also note that the transformer does not heat: it is cold.

The Commodore PET test, CBM 8032

Here, the first thing I notice is that the writing Commodore Basic 4.0 wobbles a little. I will have to inquire if it is normal or if it is a defect to be investigated. It is as if it moves left and right by a millimeter.

Also, the vendor had already informed me that the keyboard was not working properly.

Not even a button goes!

I would like to make sure the keyboard problem is not related to the motherboard. Let's see the wiring diagram.

The keyboard is managed in a similar way to that of the Commodore 64. It is scanned in rows and columns, through the integrated MOS 6520 circuit, otherwise known as PIA.

Let's do a test with a piece of electric wire. On the keyboard connector, we try to simulate the pressure of a few keys, joining, through the electric wire, a few lines with a few columns.

On the monitor... something is written! The seller was right, it's the keyboard that doesn't work.

Continues …

Soon, we will have to disassemble the keyboard is to see what there is that does not make contact, on any key. It amazes me that no key on the keyboard works. So, either all the rubber pads pressing on the printed circuit board have dried, or there is oxide. But this is only the future will tell us.

To be notified when I publish more videos related to retro computers and vintage electronics, I invite you to subscribe to the YouTube channel and activate the notification bell!